47: Are you in your Fleabag era?

On "dissociative feminism," Red Scare, and the merits of self-destruction

[TW: eating disorders]

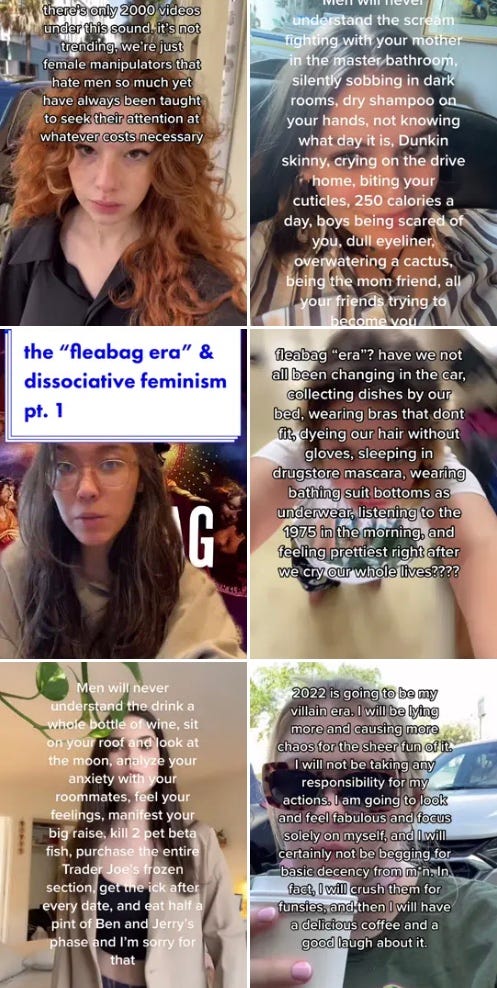

This short Twitter DM exchange between my boyfriend and me is an apt representation of the way many women are beginning to express themselves on social media as of late—a form of sometimes-humorous self-expression marked by elements of misandry, self-destructiveness, nihilism, and a tension between vulnerability and detachment. You may have seen posts or videos that start like this: “The feminine urge to…” or “Men will never understand…” Woman creators go on to describe situations they consider to be characteristic of the female experience, often trending toward messy and painful—but sometimes tender—moments. So much of this content and the worldview it represents has been classified by the makers themselves as being in one’s “Fleabag era.” If you’ve come across the traces of this way of thinking, you may have been amused, concerned, or annoyed. If you’re like me, maybe you’ve felt a combination of all three.

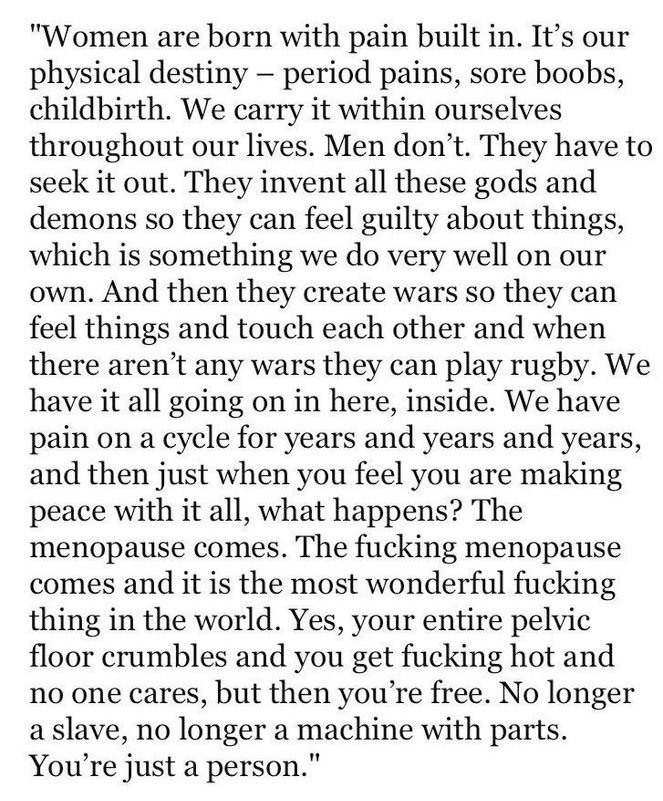

Women seem to be at this place where they invite in and even consider perpetuating hurt “as a joke” (or not as a joke!) because they are so used to experiencing it themselves. Pain underscores womanhood to such a large degree, and this especially seems to be true for women engaging in romantic relationships with men. As such, many are choosing to embrace this pain as essential and dole it out to the men who often perpetuate it, almost celebrating its internalization and externalization in turn. Celebrating the destruction of the self and other. And I find that to be incredibly interesting. Concerning, but interesting.

After the TikTok algorithm began increasingly telling me that I, too, was in my Fleabag era, I felt very seen when I came across Caitlyn Clark’s TikTok entitled “The Fleabag Era & Dissociative Feminism, Pt. 1.” Clark quotes Emmeline Cline’s Buzzfeed News article “The Smartest Women I Know Are All Dissociating” to define the Fleabag era:

“I’ve noticed a lot of brilliant women giving up on shouting and complaining, and instead taking on a darkly comic, deadpan tone when writing about their feminism. This approach presents overtly horrifying facts about uniquely feminine struggles and delivers them flatly, dripping with sarcasm. Maybe it’s a curdling of the hyperoptimistic, #girlboss, “Run the World (Girls)” feminism of the aughts, characterized by an uneasy combination of plaintive begging and swaggering confidence that gender equality was just past the horizon line. But Sex and the City and Cosmo tutorials on how to come didn’t make much of a crack in the bell jar. So instead we now seem to be interiorizing our existential aches and angst, smirking knowingly at them, and numbing ourselves to maintain our nonchalance. Let’s call it dissociation feminism.”*

[*A quick sidebar: As apt as this description of the phenomenon in question is, it’s worth noting that I don’t love the term “dissociation/dissociative feminism” and neither should you. Cline’s essay suggests that dissociation, the psychological experience of mental detachment that develops as a coping mechanism in response to trauma, can be a choice or even a performance. And that just ain’t helpful or factual, chief. As such, I’ll be using the term “dissociative/dissociation feminism” in quotes or just calling it detachment feminism throughout this piece. Okay, thanks! Onward!]

Clark and Cline identify the protagonist of the British black comedy-drama TV series Fleabag as a particularly archetypal “dissociative feminist” character. The show follows a young woman as she navigates love and life while coming to terms with an immense amount of grief and guilt. Unsurprisingly, Fleabag and those close to her do not escape the inherent messiness of bearing such a weight unscathed. Fleabag “drink[s] to excess, pick[s] fights with people close to her, fuck[s] near-strangers and [others’] lovers, diving into a seemingly infinite well of desire and emerging dripping in her own self-interest,” in the words of Cline. Yet, she does so with a self-knowing smirk. Her self-destructiveness that becomes a literal inside joke between herself and her audience as she consistently breaks the fourth wall, ever the wry architect of her own tragedy.

Clark notes that in spite of the main character’s problematic tendency to spin out of control and self-destruct with quite the blast radius, everyone wants to be in their Fleabag era. Women are clearly finding the ways in which Fleabag’s “angst is pointed internally, producing a pessimistic, nihilistic view of womanhood as naturally cursed” to be relatable—even aspirational, as we have seen. There is a sense of power, or even something as simple as an aesthetic of coolness, in turning toward irreverence in the face of pain. If women are drolly accepting their pain as inborn and inevitable, there may be an empowering sense of numbness in fully embracing that pain—in running headlong into it yourself and even bringing others down with you, if you so choose.

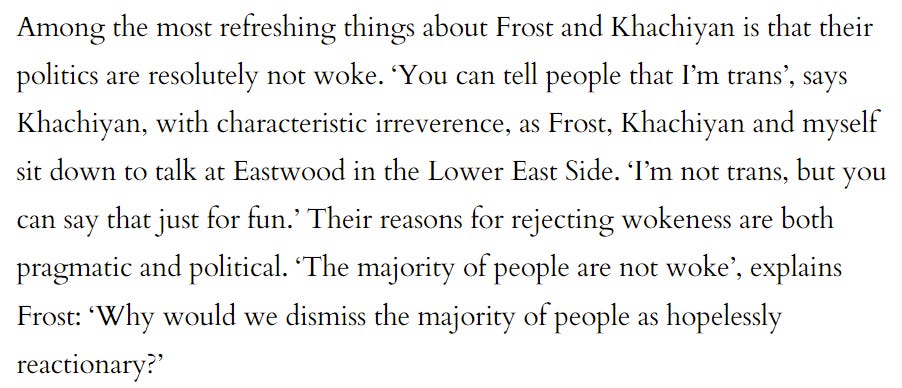

In this line of thinking, Clark and Cline compare Fleabag to Dasha Nekrasova, host of the highly problematic (and also somehow highly boring?) cultural commentary and “humor” podcast Red Scare. She’s also on Succession now—way to fall upward, queen. Nekrasova and her co-host Anna Khachiyan are loosely associated with leftism (specifically the dirtbag left), socialism, and socialist feminism. Loosely is the operative word here, as they thought it would be cool to own the libs by pandering to the alt-right and nearly dying of COVID after refusing to get vaxxed as of late. I have many thoughts. Anyway, Nekrasova has been publicly documenting her eating disorder via a second Twitter account since 2015. As Cline puts it, “Instead of starving in silence, these women tweet jokingly about the ways they live up to our unfair standards. Nekrasova, tweeting, ‘delirious anorexic coming through.’” In a similar sense, Nekrasova embodies the self-aware feminine self-destruction we see in Fleabag—her highly-publicized eating disorder is packaged as an inextricable part of her glamorous, cool girl persona. 41,000 people follow her ED account, buying into this serialized performance of her own detachment from pain. She seemingly maintains her status as a progressive intellectual precisely because she thumbs her nose at her own health struggles—even as she molds herself to fit regressive beauty standards. And she has encouraged others to do the same by publicly modeling this behavior for a growing audience over the course of the past seven years.

You can probably tell from my tone that this is where Clark and Cline kind of lost me. While I see the thread of female self-destruction that runs between Fleabag and Red Scare, the two strike me as very separate branchings off of the same impulse. Nekrasova’s public persona and Red Scare as a whole represent what Cline calls “the epitome of white feminism”—“giving up on progress […] and promot[ing] a nihilism that is somewhere between unproductive and genuinely dangerous.” Clark expounds upon this phenomenon further:

“Parts of modern feminism are turning away from the girlboss but not turning towards anything. Instead, we’re ending up in this limbo pit of despair.”

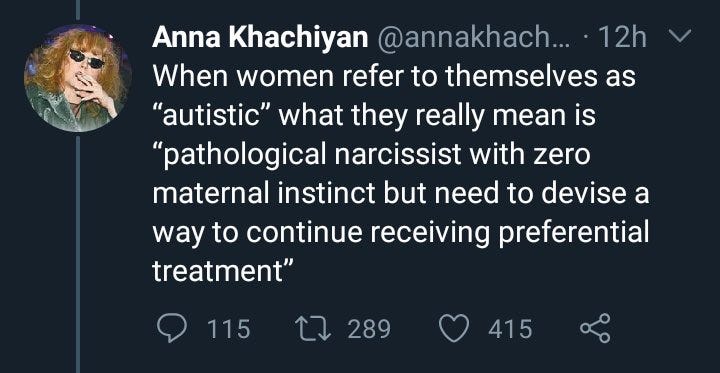

Nekrasova and Khachiyan peddle this pit of despair to us all in a way that Fleabag does not. As Anna Merlan puts it in her fantastic Jezebel article “What is Red Scare and Am I Exempt From Caring About It? A Brief Guide to the Podcast World’s Laziest Provocateurs,” they offer up “a certain kind of disaffected, supposedly leftist voice that’s casually full of breathtaking cruelty […] becoming a yet another study in how performative irony can be a vehicle for smuggling in some truly hateful ideas.” See some samplings below—neither autistic women nor sexual abuse victims nor trans women are safe from their supposedly leftist “hipster shock-jockery.” They sell their listeners an insidious façade of fake transgressiveness and intellectualism that belies thinly-veiled self-hatred, lack of hope, and do-nothingism. Their brand is marked by self-destructiveness and cheap contrarianism for the sake of being contrarian. At their big ages of 30 and 36, they are still striving to convince you they’re cerebral edgelords who are above hope, effort, or belief—that it’s uncool and unintelligent to care. All the while, there’s that nagging “weird and largely undiscussed wrinkle [… the] fact that [Red Scare] also includes some casual valorization of anorexia.” With both women publicly courting the pro-anorexia crowd with a self-aware wink, they actively yield to unhealthy patriarchal beauty ideals, modeling behavior and ideology that hates the self and hates other women for the sake of fitting into the systems keeping womankind down since time immemorial. There is nothing progressive or even transgressive about that, no matter how many layers of irony you’ve shellacked on every statement or choice you’ve ever made.

In my view, the women of Red Scare—as well as the viewpoints and lifestyles they espouse—fully represent what Clark describes as the growing danger of such strains of white feminism:

“This pit of despair, of course, is only a refuge for people who disproportionately benefit from other structural inequalities. This nihilistic post-feminist world that doesn't seek to dismantle any of the systems of oppression that we live under is only accessible to people who otherwise benefit. Specifically wealthy, white cis women.”

Nekrasova and Khachiyan are thin, white, wealthy (making over $55,000 per month just from Patreon alone) cisgender women. They are privileged enough to never have to truly challenge the systems working against women—projecting the image of being more antiestablishment than they truly are seems to be working well enough for the pair. Their painting the hope and struggle for a more inclusive and fair society as “wokeness” to be rejected on principle is a manifestation of this privilege. And it is a gross utilization of said privilege to eschew your contributions toward realizing a level of equality that fat women, trans women, queer women, disabled women, and women of color have never experienced due to a lack of drive or to maintain an aura of pick-me girl “coolness.” And to go on acting like you’re progressive despite this being the implication of your politics... Just plain sad. All I can say is that I hope we can learn precisely what not to do or to be from their example.

On the other hand, I feel that there is a good deal we can actually learn and apply from Fleabag in understanding the Fleabag era—ideas that were overlooked by Clark and Cline. In focusing in so intensely on the self-destruction that connected Fleabag to Red Scare, the two neglected to consider the arc of Fleabag as a whole, unnecessarily flattening the series. Doing all I can to avoid spoilers (you really should watch it for yourself!), Fleabag does indeed begin with our protagonist leaning into her messiest tendencies and self-destructive behaviors. But the series naturally leads to growth and an overwhelming sense of healing and wholeness—even a sense of belonging or happily being beholden to others in her community. Fleabag finally acknowledges her pain—like most women, she will never be free from it, but she has completed the self-destructive cycle after finally processing the heavy emotional load she was carrying.

I believe that many of the women declaring that they’re in their Fleabag era appreciate the unapologetic sense of self-discovery and putting oneself first that defined Fleabag’s journey home to herself—the messy joy and humor that marks her interactions with the people she loves throughout all of life’s ups and downs. I think these women are trying to communicate that they are at a low point in life, like so many of us are or have been. They are embracing the fact that they are in pain and the way out of their respective pits of despair will be inherently imperfect as a result. These women want to feel strong—to alleviate some of their pain by accepting that which is seemingly inescapable. And some might want retribution for their pain that has been caused by others—unjustly or otherwise. But I ultimately believe people are looking for exactly what the top comment on Clark’s video, with over 13,500 likes, says:

“I love Fleabag because she moves on from her Fleabag era. It’s just an era—it’s feeling your feelings, your grief. And then moving on.”

If you’re in your Fleabag era, you’re just trying to grow and heal in any way that you know how. By the nature of it being a Fleabag era, you are admitting that this cycle of self-destruction will not last forever, and you will come out on the other side of your pain closer to yourself and to those you care for. This all might run just as deep as that.

While I do think it is important to recognize the nuances that differentiate these representations of detachment feminism in popular culture, it is also important to circle back to what this “Fleabag era” phenomenon says about the swaths of women seeking out sometimes-self-destructive idols and lifestyles in their search for post-feminist meaning. Clark argues we’re witnessing a response to the failures of “#girlboss feminism that promoted women as being capable of achieving gender equality within our lifetimes”—that the development of a more nihilistic, detached form of feminism seeks to tear down the girlbosses and their shiny, empty promises. To harden oneself against the pain of acknowledging the perceived lack of progress with the feminist project. But Clark makes a necessary distinction about this manifestation of our collective outrage: “Girlboss feminism didn’t serve our collective liberation, but neither does this nihilistic feminism.” We can surely see the danger of this backsliding in Red Scare’s aesthetic of do-nothingism—and in its growing popularity. Helpfully, though, Clark suggests that “the very fact that the feminist movement is constantly coming into contradiction with itself proves that it’s continuing to develop further from here.”

If this self-destructive feminine impulse is eventually channeled toward the systems working against us, we’ll be on our way to collective healing and empowerment. As with the cycle of healing presented in Fleabag, this era of uncertainty will pass. But not if we sit idly by, numbing ourselves to the pain of the world just because it hurts to try and to fail and to try again. Let’s continue doing the dirty work required to improve our lives and the lives of others (especially if we are privileged enough to even consider detaching from the impulse to make change or make good!), embracing the mess that comes with wading into that uncharted territory. Anything is an improvement upon unrelenting girlbossery or promoting self-destructive patriarchy-sanctioned eating habits to own said libfems. It’ll pass. We’ll make it so. Now, onward to anywhere that is not here!

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney. I so respect the way this book attempts to capture the tension of living in the present moment—the lack of ethical answers you’re faced with while living in a world full of so much pain and so little discernible meaning. I think it’s a super ambitious step forward for Rooney in writing toward a more explicitly Marxist novel, and a lot of the ideas she puts forth are very timely and interesting. But most of all, I appreciated it so much for its representation of a deep, modern female friendship. The protagonists sustain their friendship across time and space by writing to one another, making this story hit especially close to home for Anna and me as that’s essentially what we’re doing with TWHI. We actually happened to read the book at just about the same time, which made the entire experience extra special. Some quotes that rang true for us:

“I never know what to think until I talk to you.”

“I just want everything to be like it was […] and for us to be young again and live near each other, and nothing to be different.”

“If you weren’t my friend I wouldn’t know who I was.”

Beef vindaloo. It’s been so cold here, and curry has really hitting the spot as a heartier (and spicier) alternative to soup. Sometimes I forget that you really can just order multiple servings of a meal for yourself from a restaurant and save them for later like leftovers. The world is your oyster. I definitely did that with a local Indian restaurant and it was a fantastic call—highly recommend stocking up on meals you like if it makes sense for you and cooking is an endless torture you refuse to partake in most days of the week!

Bananagrams. This is quite possibly my favorite game of all time—or it might just be the one I’m best at. Who’s to say?! I replayed Bananagrams for the first time in a long time while on a little birthday getaway with Alex. We played games long into the night, and I beat him three times, defending my title as the undefeated Bananagrams champ. An absolute thrashing. The wins felt really good because he beat me at Trivial Pursuit not too long ago and my pride has been wounded ever since. Anyway, love the simplicity of this game, its quick pace, and its promotion of creativity. And it comes in a banana-shaped pouch! What else could you ask for?!

Dungeons & Dragons. Fun fact: Alex is a very passionate Dungeon Master. As such, he has been trying to convince me to play DnD for over a year now. I am a very non-performative, non-improvisational, and sometimes very shy person, so this has essentially been a threat looming over my head up until I finally gave in and played. Alex and his friends are incredibly kind and welcoming, and I’ve found that I genuinely can enjoy myself! Playing DnD is truly a super unique experience—I don’t know of many other opportunities to engage in collaborative, immersive real-time storytelling with friends in such a way. All in all, the fact that I am doing a silly voice and not hating everything is a big deal.

Fancy cheese and wine nights. The other night, I had Anna over to my apartment and we ate fancy cheeses (both vegan and nonvegan) and drank white wine until the wee hours of the morning. We stayed up until 3:30 am after talking for nine hours straight—laughing, crying, having intellectual discussions and then saying the dumbest shit imaginable in the next breath. And we had our first sleepover in a long while :’) It was a great reminder of why we are friends. Elite quality time! Never running out of things to say! Live, laugh, love!

Ultra compelling read! I got sucked into this at work! Keep it up y'all 👍🏻

These women are narcissists and so is the character on Fleabag. Fleabag is a terrible representation of women. Sorry but as a woman, I don't relate to what you're talking about at all.